This book shows how the mysterious art of film editing is actually done, by using the “out” and “in” frames of the actual cuts from classic movie scenes — namely The Graduate, Chinatown, Rear Window, The French Connection, Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid, The Big Chill, A Hard Day’s Night and Body Heat.

The following scene from The Graduate is a case in point.

The set up:

Benjamin, (Dustin Hoffman) a recent college graduate, has left the party his parents threw in his honor because Mrs. Robinson (Ann Bancroft), a friend of his parents, has pressured him into driving her home. Mrs. Robinson leads Benjamin into her den and offers him a drink and before he can respond, she’s pouring him one. In this key scene, Mrs. Robinson pulls Benjamin in, first with her neediness, then with her increasingly candid confessions, and ultimately with her sexuality.

As the editor, Sam O’Steen, explained, “The theme was a jungle. You can see it in the plants, in the furniture, she was even wearing a jungle print. She was like an animal trying to devour him.”

We, the audience, know that Benjamin is way over his head, and we can pretty much see what’s coming, which makes it painfully funny to watch and wait for him to “slip on the banana peel.” The approach is not completely objective, however, since we identify with Benjamin and see some of what she’s doing through his eyes as well. As a result, the conniving Mrs. Robinson is always one step ahead of Benjamin and even a bit ahead of the audience.

In the shooting of The Graduate the filmmakers paid a great deal of attention to composition within the frame, which was not only visually innovative but had dramatic and comedic resonance. In this particular scene, there’s an unusual amount of foreground and background emphasis, with great discrepancy shown in the size and height of the two actors within the frame, symbolizing Benjamin’s insecurity and discomfort relative to Mrs. Robinson’s power over him.

There are four comic/dramatic arcs in this scene:

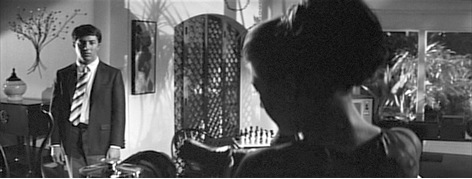

The first arc comes after Benjamin tells Mrs. Robinson he’s leaving. In this shot (shown in Frame grab #1), Benjamin is in the foreground, the larger figure, when he still has some control over the situation. But then she says, “Please wait till my husband gets home,” and now Benjamin is thrown, because if she’s afraid to be alone, how can he say “no”? The editor makes the first cut here, because it’s a turning point, the first step to Mrs. Robinson’s entrapment of Benjamin. He cuts to a shot (the “in” frame is Frame grab #2) where her back is to the camera, in the foreground, with Benjamin in the background, looking much smaller than she. The focus is also on him, putting him on the spot visually and psychologically.

Frame Grab 1

Frame Grab 2

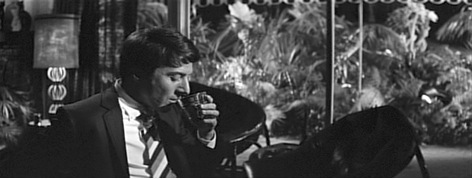

The second arc occurs when she says “I’m very neurotic,” which throws him even more. The editor holds on this shot, where she dominates the foreground and he’s in the background, while she blows smoke in his face, and he ineffectually tries to swat it away. When he sits down and she leaves him alone, the editor decides to stay on him at that distance in the long shot to underline his discomfort. The editor could have cut to a medium long shot of Mrs. Robinson over Benjamin, which booms down with him as he sits down [Slate 14] but his isolation and impotence wouldn’t have been felt as much. The editor continues to hold on Benjamin, who’s looking small and helpless, as Mrs. Robinson plays the dramatic, seductive music (the “out” frame of that shot is Frame grab #3).

An insert was shot of Mrs. Robinson putting the record on the phonograph [Slate 109], but this would not have been as effective for two reasons. First: holding onto him as the seductive music comes on and he jumps to attention is a very funny, awkward moment; to cut away would have weakened its impact. Second: if the editor showed her actually turning on the phonograph, he would have had to let this scene play out more in real time. The audience doesn’t notice or care that in real time Mrs. Robinson could not have left Benjamin, turned on the music, and headed back to the bar (the “in” frame is Frame grab #4) in the three-and-a-half seconds of screen time it takes. The tension and humor is more effective because the editor made this cut in movie time.

Frame Grab 3

Frame Grab 4

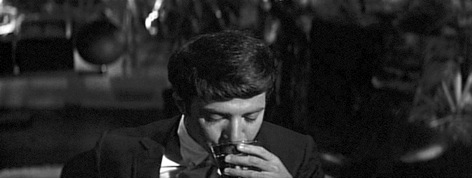

The editor sets up the third arc with extra beats. Mrs. Robinson provocatively asks Benjamin what he thinks of her. When he answers that he thinks she’s a nice person, the editor holds for a beat on Benjamin, letting him start to sip his drink, relax, and let his guard down (the “out” frame is Frame grab #5). When the editor cuts to Mrs. Robinson, he gives her a beat before she responds, showing her dissatisfaction with his polite answer, and her mind turning while she chooses what to say. This beat also sets up the impact for the third arc, when she says, “Did you know I was an alcoholic?” (the “out” frame is Frame grab #6). This line is shockingly intimate and throws Benjamin off guard even more.

Frame Grab 5

Frame Grab 6

After her dialogue, when the editor cuts to Benjamin (the “in” frame is Frame grab #7), his head is all the way down; he’s in the middle of innocently swallowing his drink. That gives him a chance to look up, gulp his drink, and do a double take, thereby milking the moment. This is the first time the editor has chosen to use a close-up in this scene; he’s saved it for when it really counts. The dialogue is also the tightest on this cut, from her “alcoholic” line to him, almost overlapping, because it’s such a tense moment. In fact, the close-up is the only head-on angle used in the scene. When Benjamin was in the more distant medium shot previous to this (Frame grab #5), the editor could have used a head-on angle [Slate #106] instead of the profile, but he saved the double intensity of the straight-on close-up for Benjamin’s significant reaction. For the next shot, the editor chooses the first close-up of Mrs. Robinson (the “out” frame is Frame grab #8) to reinforce the startling intimacy of her confession: “Did you know that?”

Frame Grab 7

Frame Grab 8

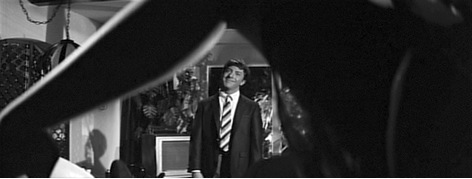

In the next shot, which again starts close on Benjamin, he’s reacting strongly, but this time he’s in a panic. He bolts out of his chair and says, “I think I should be going.” In the “out” frame of this shot (Frame grab #9) the editor violates the action-cut rule that says that when an actor is standing up, cut out before the actor’s face leaves the screen and definitely before we see only his midsection (which is the case here) because the shot will seem stale. In this instance, however, the editor is using the momentum of his motion to effectively cut out of that shot. Benjamin has just started standing up straight, and then in the next shot (the “in” frame is Frame grab #10) he’s already at the bar, even though he was some distance away. (Note the distance between where Benjamin is sitting and Mrs. Robinson’s bar stool in Frame grab #3.) Also, in Frame grab #9 he’s facing the camera, his arm by his side, and in Frame grab #10 his back is to the camera with his arm outstretched.

Frame Grab 9

Frame Grab 10

This mismatched action and potentially awkward cut feels smooth because the editor cut out and then in to the next shot when Benjamin’s energy is at its peak. And even though we don’t see his glass, the sound of it being plunked on the bar at the beginning of that second shot gives the cut better flow.

Also, the audience’s eyes follow Mrs. Robinson rather than Benjamin in the second shot, because we see she means business when she says, “Sit down, Benjamin.” The result: the audience doesn’t notice the jump cut from Frame grab #9 to Frame grab #10, due to the visual momentum the editor created and our desire for him to be there at the bar right away to keep the tension going in the scene. Within the same shot, Benjamin walks away toward the camera, trying to get away from Mrs. Robinson, and he ends up in silhouette in the foreground (we can’t see his face). He paces and confesses his suspicions of her (the “out” frame is Frame grab #11). The editor could have cut to any number of shots: a big close-up of Benjamin [Slate 21], a medium long shot to Benjamin [Slate 22] or close shots of Mrs. Robinson that were already used. But the editor chose to stay with this shot through quite a bit of dialogue, because it’s working so well, the composition and staging perfectly capturing the situation. The visual emphasis is on Mrs. Robinson in the background when she is at her most seductive, poised on the bar stool with her legs parted, while Benjamin in the foreground is a shadowy figure, nervously pacing.

Frame Grab 11

When the editor cuts to the next shot of Benjamin seen through Mrs. Robinson’s bent leg (Frame grab #12) the audience experiences the final and most dramatic arc of the scene. It’s when Benjamin says the most memorable line of all: “Mrs. Robinson…you’re trying to seduce me.” The shot itself is also the most famous one in the movie, but in fact, the camera angle is not realistic at all. For one thing, it doesn’t make any sense as a reverse shot. Even though she has her foot propped up on the bar stool in a previous shot (Frame grab #11) the position and angle of her leg doesn’t match with this subsequent shot. In fact, she would have to be a contortionist to sit at the bar and have that angle through her leg really happen. But by putting him in this position inside her bent leg, the editor makes Benjamin looks smaller and more pathetic than in any of the other foreground/background shots. The contrived composition works well to exaggerate his powerlessness and the surreal situation. (There was actually another shot [Slate 21] a close-up of Benjamin through her leg, with variable focus which wouldn’t have been as funny, because he wouldn’t have been as clearly small and ridiculous.) The editor then cuts to Mrs. Robinson laughing (the “out” frame is Frame grab #13).

Frame Grab 12

Frame Grab 13

This is the only other instance beyond the alcoholic confession that the editor chooses to be close on Mrs. Robinson. This close-up of Mrs. Robinson does not match at all with the shot of her at the bar before this shot. It’s actually a “pickup shot,” meaning a portion of the angle filmed to supplement the original shooting of the same angle, usually because the original coverage was inadequate. In this shot, Mrs. Robinson’s head is thrown back, her eyes are closed, and her mood is much more animated. Obviously the editor wanted this particular reaction, because it has such an unnerving effect on Benjamin and leaves him so vulnerable. Was she trying to seduce him or not? Even we, the audience, can’t be sure what the laugh means. It’s one of those moments where we’re ahead of Benjamin but not completely ahead of Mrs. Robinson, although we suspect it’s part of a ploy to make Benjamin feel guilty and embarrassed and become putty in her hands. This close shot also doesn’t match up with the subsequent pickup shot of Benjamin and Mrs. Robinson (the “in” frame is Frame grab #14). Her hand is not touching her ear anymore, and her head is more upright than that previous pickup shot. But the audience is focusing on the mortified reaction of Benjamin, who again looks powerless in this foreground/background composition.

Frame Grab 14