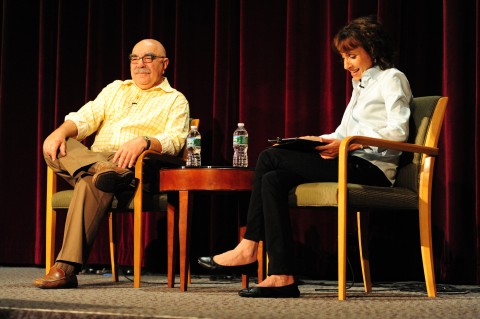

Bobbie and Alan at EditFest NY

I just moderated my third panel for EditFest, and although this had only one panelist, it was enough for a feast, because that panelist was the very gifted and gracious Alan Heim. Alan chose to discuss and show clips from Star 80, director Bob Fosse’s final film, which was an unconventional decision. The film was vilified by the critics and audiences found the disturbing and sexually violent subject matter to be difficult viewing. Alan said, “I believe had it not been so well made, maybe it would have been unwatchable.” Fosse had this to say about the film: “The passion I had when I made it is no longer there, but I know it’s technically the best movie I’ve done. I felt completely in control of this story.”

Fosse was known as a brave visionary, which can be also said about Alan. On the first of over forty films Alan edited, he got a taste for taking risks. The director was Sidney Lumet, who came from live television and was known for shooting very few takes. Out of necessity, Lumet showed Alan what you could get away with, how you could take chances, which got his juices going.

When Alan met Fosse in 1972 he said, “I discovered in Fosse a really kindred spirit. The whole freedom of editing that I got from Bob fits into my whole psyche.” Their first venture together was Liza with a Z which was a one hour live concert, filmed with nine cameras, “A tremendously complex film and the main camera broke in the middle of the first act, so we had no master shots and we started fiddling around with the film to cover that. And we sort of never stopped fiddling.”

The next film they did together was Lenny, about comic Lenny Bruce, “one of the best scripts I’d ever read.” But when Alan started cutting it together, Dustin Hoffman’s performance, “was kind of weak.” Alan suggested to Fosse “that we intercut it more than it had been intercut in the script, his performances with his life. So suddenly I was really making juxtapositions that told very strong stories. I always felt working with Bob was a little bit like working on a silent film. The dialogue wasn’t really all that important, you just kept moving.”

Then Fosse went on to write and direct All that Jazz (for which Alan won an Oscar) and he used the techniques they used in Lenny. “It had as much interconnectedness as Lenny ended up having”, which was followed by Fosse writing and directing Star 80, “a tremendously complex movie.” So not only was Lenny made in the cutting room, but it created a kind of template for the next two films.

All three films have more than an intertwined structure in common. They’re all based on true stories and on some level deal with Svengali situations: the man behind the woman. They also deal with the dark side of showbiz and the human condition. And – as Alan said – they have, “at the end, a dead body.”

Star 80 was based on a Village Voice article about the killing of Dorothy Stratten, who was discovered at a Dairy Queen in Vancouver by a small-time hustler named Paul Snider, who became romantically involved with her and persuaded her to pose for nude photos. She ended up in Los Angeles as a Playmate of the Year and an actress and was eventually killed by Paul, “out of jealousy and a kind of a madness…So when we made it we felt the audience would know the story and we had a certain freedom to mess around with time. The other thing was that Bob loved to mess around with time. Ralph Burns [the composer] who worked with Bob a lot, said, ‘There’s real time and there’s flashbacks and there’s flash forwards – and then there’s Fosse time.’… It shows what you can do if you are willing to trust the audience, give the audience as little information as you can in a way, let them discover things, and then move on, and try and weave it together.”

We ran the first five minutes of the film, which showed the dense embroidery used to tell the story. Dorothy’s voice-over interview about her life as a Playmate is cheerful and innocent, as we hear the clicking of the tape recorder and see a montage of photos of her posing for Playboy. Then we see a nighttime shot of swirling traffic lights and ominous music, along with a bloodied and agonized Paul in front of a blowup of one of those Playmate photos, a snippet of the murder scene. There is no real suspense, because right away we know what is going to happen – and that this narrative is doing something very different.

Certain elements here will recur throughout the movie as a way to fracture and punctuate time. The bloodied Paul at the murder scene, the documentary-like on interviews with Dorothy, the clicking of the tape recorder and the camera shutter, the montage of photos showing her early life and Playboy shoots. (Fosse had used recurring motifs in All That Jazz, such as showing the main character repeatedly popping pills, smoking, using eye drops and antacids, then looking in the mirror: ‘It’s showtime, folks!’)

The next scene is a flashback to Paul at the beginning of the story, lifting weights and posing in front of the mirror, which tells you virtually everything you need to know about him – the slippery slope he’s on, his lack of self-awareness, the hollowness of his talking to himself in the mirror, his ultimate disappointment in himself. (There were always mirrors in Fosse’s movies, as well.) As we watched the montage of Paul working out, we got to experience Alan’s magical way of cutting to music, which eludes explanation, but has been partially described as being: not on the beat or off the beat but around the beat. We also then see Paul as a sleazy entrepreneur, staging a wet T shirt contest. Fosse was a dancer – originally in the world of burlesque – which somewhat explains the mirrors and his fascination with the sleazy aspects of show business.

Part of the reason why Star 80 drew such harsh response was because the audience wanted to hate Paul Snider, but Fosse was really targeting show business and how it can destroy people. As Alan said, “He felt there’s a lot of treachery in show business and a lot of people who would put a half a scissor in your back, an editor’s term, we used to use scissors.”

Paul Snider is also more complicated than a cardboard villain. Fosse actually said to Eric Roberts, the actor who played him, that the character is really Fosse himself, if he hadn’t become successful. Alan said, “I had never worked on a performance where the actor was so prepared.” He never went out of character during the whole shoot. “It was scary.” And Alan captured his intensity in the editing, “all the way through.”

What’s most striking about this opening sequence is that the transitions are so beautifully realized. Before he became a director Fosse had not only been a dancer but a great choreographer, and there was a kind of choreography, a movement of images within the frame and from shot to shot, that was truly inspired. Alan also talked about making “Fosse cuts” where the angles don’t match, where the cuts are sharp and take you to a completely different place. This works, though, only if you have the finesse to pull it off. “When you edit a film, transitions are always difficult,” says Alan, and Fosse’s must have presented a particular and inspiring challenge.

“In that [opening] scene, the camera was moving and the cuts came at certain points, the still shots in the middle of moving cameras – but it was an enormous amount of emotion, and I think when you’re editing a film, the trick is to keep the audience interested as long as you can, and then just make the decision to move on to the next…The editor has to find the right place to push the audience into the next scene and that’s the hard part about working on a film, you just can’t expect to follow the script.”

The next clip we showed was an hour and 14 minutes into the movie, and it was after Dorothy had begun an affair with the director she was working with. Alan mentioned another recurring Fosse moment: of a radio, followed by a kind of horizontal move across revealing the actor’s eyes. In this case the focus is on Dorothy’s eyes, who’s in a sort of trance, and in the background is the director who is gently pushing her to leave Paul. He may be nicer than Paul, but again a man is manipulating her. Paul sensed that there was an affair going on and in the next scene hires a private detective who confirms his fears. Then he buys a gun. “The clicks and the shutter that we’ve heard all along throughout the picture are now echoed by the shotgun, that click of loading the gun. So everything was tied in.” You see how they also echoed the structure of this scene – Paul cocking the gun, putting it in his closet – with what’s coming up.

The last clip we ran was the scene leading up to the rape and eventual murder, which takes place in the apartment Paul and Dorothy actually lived in and where the murder took place. Again there the backdrop of the blown-up Playmate photo, we see Paul desperately trying to hold on to Dorothy and she stays just long enough – because of a mixture of pity and loyalty – for him to rape her, kill her and then himself. “We shot that at the very end because the actors didn’t want to do it, the producer and I would try to get Bob to back off a little bit on the blood and some of the sexuality of it. He did what he wanted to do. Later, he said he probably should have backed off on the blood a bit, I don’t know if it would have been better or not.” At a special screening for Star 80 people left just before the bloody rape scene. This also happened during the heart operation in All that Jazz. Fosse’s comment: “Well, I guess we reached them.”

Alan’s depth of feeling for Fosse is obvious, his admiration for this remarkable artist who embraced his own vision, told stories the way he wanted to tell them.

Alan said, “I was incredibly fortunate, to work with the material of, what I regard a genius, really. He made so few movies and I was able to take advantage of that, just working with a guy like that with material like that. You don’t get it too often. “

Fosse wanted those he worked with to “dig deep into ourselves. He made you work hard, and what was so nice about working with him was he always acknowledged it.”

I mentioned that Fosse had called him a “collaborator.”

“To be called a collaborator by a guy who I think is such a brilliant filmmaker was absolutely wonderful. And also he had occasionally referred to me as his conscience and I like to think as an editor that’s what I do. Sometimes you have to just shake somebody up and say ‘You know, it’s not working. You might love it, but it’s not working. And of course it’s not enough to say that, you have to have a solution, too.”

Well, I imagine Fosse felt it was pretty wonderful, too, having Alan as a collaborator – and a conscience.