Bobbie Interviews Editor Craig McKay

Article on homepage of MovieMaker Magazine: “An Editing Revolution”

Editors Sam O’Steen and Dede Allen never met, but a shared aesthetic led to some of the most ground-breaking films of all time

by Bobbie O’Steen | Published November 18, 2010

L to R: Carol Littleton, Bobbie O’Steen and Jerry Greenberg discuss the impact of Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen’s work.

Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen never met, but at one point they were both in cutting rooms at the same time overlooking Times Square; and they were both working on films that would change the landscape of editing forever: Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate.

Rewinding on their lives and careers reveals other interesting parallels. They were born about a month apart and experienced significant hurdles on their paths to success. Dede was 34 when she cut her first feature, and Sam was 39. Dede’s legendary body of work includes The Hustler and Serpico, and she received Academy Award nominations for Dog Day Afternoon, Reds and Wonder Boys. I had more direct knowledge of Sam’s career, since I met him in the cutting room and was married to him for 23 years. We also wrote a book about his 45 years of editing, which included his work on such films as Cool Hand Luke and Rosemary’s Baby. He also received three Academy Award nominations for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Chinatown and Silkwood.

Dede was not nominated in 1967 for Bonnie and Clyde, the first of six films she edited for director Arthur Penn, nor was Sam for The Graduate, the second of 12 films he cut for director Mike Nichols. The L.A. Times called this a “spleen-busting travesty,” but it was not all that surprising since their editing techniques on these maverick films were definitely outside of the Hollywood mold.

A.C.E. generously allowed me to honor Dede and Sam and their trail-blazing work last August for EditFest LA. I was also able to convince two other remarkable editors—Jerry Greenberg (Apocalypse Now; Scarface) and Carol Littleton (E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial; Body Heat)—to join me in paying tribute.

Jerry was the first of “Dede’s boys,” one of many young editors Dede mentored who went on to have great success in their own right. Carol Littleton also has a reputation for mentoring young talent and, after having interviewed her extensively over the years, I knew her to be particularly articulate about the elusive art of editing.

Jerry started off talking about how inspiring it was to work with Dede between two Moviolas, experiencing “not only what was on that person’s mind, but how their fingers work, how their body works. In the days of the Moviola, you not only did the housekeeping, but the second thinking.”

The three of us discussed what it meant to edit a film in 1967, particularly in the case of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, since post-production took place in New York, away from the control of the studios. This was also a time when studio influence was waning and directors were given more freedom to express their visions. Editors were also acquiring more stature and, in fact, Dede and Sam were the first to get single-card credit that year.

American audiences were also changing: Forty-eight percent of them were under 24 and many were college-educated, rebelling against social injustice and the “falseness” of their parents’ values. The audience, as well as the filmmakers, was also exposed to foreign films; they were especially taken by their personal narratives and experimental style. So on many levels, Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the time.

The first clip we showed was the first 10 minutes of Bonnie and Clyde. The opening shot is an extreme close-up of Bonnie’s (Faye Dunaway’s) lips and then there are a series of jump cuts, showing her naked in her bedroom and looking imprisoned, through the bars of her bed frame, revealing both her vanity and restlessness in this small Texas town. She spots good-looking Clyde (Warren Beatty) trying to steal her mother’s car and soon they are walking down the street, with Bonnie coming on to him.

The way she licks the rim of the coke bottle and strokes his revolver, “This is just outrageous,” says Carol. “In lesser hands this would be so arch, but it’s done so well. So much is contained in this one moment.” Right away we see Bonnie’s charged sensuality and Clyde’s uneasiness with his body and his sexuality—and, as Jerry says, “two characters searching for something that was missing in their lives in the middle of the Depression.”

The whole sequence “works on so many levels” and yet, as Carol says, “everything that happens is a surprise; subtle, but a surprise.” Next, we see Clyde rob a store and steal someone’s car. And then, Jerry says, “You think it’s going to be something and it’s something else. First, there’s this loose shot of them wending down this road away from town and this banjo music playing and then the next cut is passion, she’s all over him… In the editing of the scene, this in and out of very tight and loose shots… Dede played on all of that; she knew how to do it, to shock you and not shock you.”

The next clip we showed was the iconic death scene, the end of the film, where Bonnie and Clyde are ambushed by police, with a barrage of bullets. Jerry explained that he initially cut many action sequences on a picture-only bullet head Moviola. Director Penn used four cameras for every setup, each one filming from the same angle but running at four different speeds. “Arthur Penn said to me, ‘What I want you to do is try to make this as orgiastic as you can. I want it be abstract enough so that what they never accomplished in the years that they were together, they accomplished here. This was the sex scene.’”

Who can forget that powerful close-up of Bonnie looking passionately at Clyde, the moment before the onslaught. “And as I see it now, it was like The Wild Bunch.’You don’t see all of that dying as anything but abstract. It’s not horrible enough to turn way. You have to open your eyes wider because something else is happening.” Bonnie’s rag-doll dance of death, intercut with Clyde writhing on the ground, was like a ballet, “a pas de deux” says Jerry. “The editing technique, mixing slow motion and fast motion and close-ups and loose shots, Dede was a master—a mistress—of that. She knew how to make it work better than anybody I know.”

Dede also called Jerry’s contribution, “brilliant.”

This high-wire act of mixing sexuality, comedy and violence was also evident in The Graduate, with maybe no physical violence in the latter case, but very dark emotions. Both sets of characters also played an intriguing game of cat and mouse.

Sam’s role as editor on The Graduate was unusual because he was on the set for the entire shoot, something he would do throughout the 28 years he worked with Nichols. Because he was involved in the layout of every shot, he had the luxury to help plan transitions and compositions within the frame that would make the most of the anamorphic widescreen, which hadn’t ever been done so effectively for such an intimate story.

The first clip of The Graduate starts 10 minutes into the film, when we see college graduate Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman)—having felt “suffocated” at a party his “plastic” parents threw in his honor—coerced into driving Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft) home. The subsequent scene in her den makes full use of foreground/background staging, capturing her escalating control and seduction. Every time she turns up the heat, Sam cut to angles that show Benjamin looking smaller and more powerless. This culminates in the classic shot of him “inside” her bent leg, saying, “Mrs Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me.”

“Sam and Mike really knew how to mix their punches,” says Carol, “in the same way that Dede and Arthur did in Bonnie and Clyde. It’s never a clean straight path and we’re constantly being drawn in and pushed back… Using the camera and image size, all the tools filmmakers have.”

When Mrs. Robinson finally traps Benjamin in the bedroom—and she’s naked—the tempo and the style of editing changes. Benjamin’s head swings around three times, to express his “triple-take” moment of shock. Sam used subliminal cuts of her breasts and stomach, discovering that three frames expressed Benjamin’s can’t-look-at-her-can’t-look-away reaction. He initially cut the rest of the scene using close shots of Mrs. Robinson’s face proposing an affair and close shots of Benjamin. But it wasn’t funny. So Sam decided to experiment and use an outtake, which was shot past Mrs. Robinson’s shoulder, to Benjamin’s face. That version is funny because her disembodied off-screen voice makes the moment more surreal. And Sam knew that Dustin Hoffman’s consummate performance held up, hilariously.

The next clip we ran is a five-minute montage showing the progression of their affair, starting with Benjamin floating in the pool surrounded by a “prison” of sparkling water. He then enters his house and on the other side of the cut, instead of seeing the interior of his house, we see, in a meticulously matched shot, that he is entering a hotel room. Sam continued to cut seamlessly between hotel and house and back again, by using close-ups of Benjamin against black backgrounds—a headboard, a chair and a pillow—all showing his expressionless face “float” numbly through this relationship. The use of pre-released songs—from Simon and Garfunkel albums—was revolutionary, something that had never been done before. And Sam used two songs back to back, which worked because they both expressed what Benjamin’s character was feeling.

As Carol said, “The basis for both these films is about searching for an identity… They are extremely involved in the intricacies of psychology—and they’re unbelievably entertaining.”

Jerry made a very insightful observation at the end of our panel, about “something that struck me in these clips… Two shots. It implies that they’re interacting with one another. Which is used to greatest effect here, because I almost expect to see a cut in the middle of the dialogue, to a reaction shot, but I appreciate that there was no cut there, that it stayed on that two shot.”

Carol said that Dede’s and Sam’s work revealed “incredible vigor and confidence.” They often made brave choices, but they also “had a sense of measure, of knowing when enough is enough.” And to only cut when there’s a reason.

“A good cut is when you do not see it unless you want to,” Dede once said.

“You’re trying to tell a story,” said Sam. “It’s not about somebody showing off.”

![]()

Bobbie O’Steen and Tim Squyres discuss and show his editing of Gosford Park. (Part 3)

Bobbie O’Steen and Tim Squyres discuss and show his editing of Gosford Park. (Part 2)

This is part two of a three part series. See the original post here.

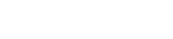

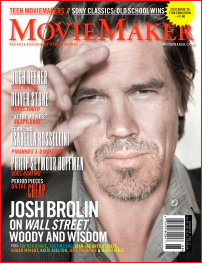

Check out my article in the latest issue of MovieMaker Magazine: “A Tale of Two Editors”

A study in contrasts between two editors (Carol Littleton and Tim Squyres) who used their own unique methods and sensibility to shape the footage from two very different movies and their directors (Lawrence Kasdan’s “Body Heat” and Robert Altman’s “Gosford Park.”)

The Editor Leaves His Mark on ‘Michael Clayton’

Read the article here.

A Tribute to Two Trailblazing Editors: Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen

Carol Littleton, left, Bobbie O'Steen and Jerry Greenberg.

A Tribute to Two Trailblazing Editors: Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen

Moderated by Bobbie O’Steen

Jerry Greenberg, A.C.E. (The French Connection, Apocalypse Now), Oscar winner Carol Littleton, A.C.E. (E.T: The Extra Terrestrial, Body Heat), Emmy winner, Oscar-nominated

A Tribute to Two Trailblazing Editors: Dede Allen, A.C.E., and Sam O’Steen, A.C.E., moderated by Bobbie O’Steen with panelists Jerry Greenburg, A.C.E., and Carol Littleton, A.C.E., was a genuine treat. From tales of what it was like to work with Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen to analyzing scenes from Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, it’s not often that you get this level of candor, insight, analysis and humor. The panel really was one for which “you just had to be there,” so what follows are some excerpts from the conversation and scene analyses.

O’Steen began with a round of thank yous to panelists Littleton and Greenberg. “It’s a true honor to have them help me pay tribute to these remarkable editors,” she said. “It’s a feast of talent in memory and in reality today.” O’Steen gave extensive bios on both Allen and her late husband, O’Steen. She explained that she had conducted extensive research on Allen, but didn’t have to do the same for O’Steen––because she met him in the editing room and was married to him for 23 years.

“I think Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen took different paths in their careers but there were some interesting parallels,” she said. “Here you had two editors who were passionate and determined. Both had a hard time breaking into the business. They had hurdles and they overcame them.”

And then the conversation focused on Allen. In addition to being a pioneering editor who revolutionized editing, she was known as a great mentor. Greenberg has the distinction of being the first of “Dede’s boys,” as they were called. O’Steen asked Greenberg what it was like to be an assistant under Dede Allen––specifically, “What it was like standing between two Moviolas with Dede?”

“She didn’t have to say anything; it was what she did,” Greenberg responded. “In those days, you could sense not only what was on that other person’s mind, but how their fingers work, how their body works; you got it all. That was the best way to get to know one another––and also to anticipate what that person was trying to teach you by doing. Obviously, the nature of how things get done now is very different; there is no assistant. In the days of the Moviola, you [the assistant] did all of the housekeeping but you also did the second thinking, and that I know is missing now.”

Before looking at some clips from two seminal films––Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate––edited by Allen and O’Steen, respectively, the moderator set up the

social/cultural context: The year was 1967, a time when studio influence was waning–– which was good for the two editors. Directors were becoming more empowered and expressive in their artistry, and, as a result, editors were also acquiring greater stature and recognition. Both those films were edited in that very crucial stage away from the studios.

O’Steen had asked Littleton and Greenberg to watch the films in preparation for the panel and solicited reactions. Littleton commented first: “It was very interesting to see them both back-to-back, primarily because I was in college when I saw these for the first time, and they became sources of inspiration for me. There was something about both of them that they were so fresh, so different and wonderfully enticing. I had the same feeling watching them again.

At the basis, these films are about searching for an identity and they are extremely involved in the characterizations and the intricacies of psychology and how these people work––and they’re unbelievably entertaining,” Littleton continued. “So it’s an incredible thing to make a film that works on those levels; we have to be concerned about when we’re cutting––on the level of plot, the level of characterization, and narrative push or narrative flow. Both of these films are more than artful; they’re strokes of downright genius as far as I can see.”

Greenberg said that watching the opening and final scenes from Bonnie and Clyde brought back memories. “I was there when the film was being edited,” he said, adding that he hasn’t watched the film since then. “That was 1967 and I choke when I say that; it’s so long ago, and yet the editing technique of mixing slow motion and fast motion, and close-ups and loose shots and all of that stuff…Dede was a mistress of all of that. She knew how to cut faster than anyone I know––and make it work.” That’s the difference.

Moving on to The Graduate, O’Steen said that Sam, longtime collaborator with Mike Nichols, was always on set for the layout of every movie he did with the director. She explained that Sam could do this because he was such a fast cutter.

“He was able to let the film stack up in the cutting room for about the first six weeks of shooting,” she said. “Then, whenever there was down time on, the set he would just cut.” Part of that reason was because he never looked at anything he cut before he showed it to a director, unless there was a specific technical problem, O’Steen revealed.

The audience was treated to two scenes from The Graduate. During the scene analysis, O’Steen pointed out the way that Sam used subliminal cutting, the use of composition within the frame to tell a story, and the use of transitions to get from one place to another. Also unheard of at the time was using the pre-released music of Simon and Garfunkel.

Read the Editors Guild coverage of my panel at EditFest LA here.

Bobbie O’Steen and Tim Squyres discuss and show his editing of Gosford Park. (Part 1)

Bobbie O’Steen and Tim Squyres discuss his editing of Gosford Park.

When director Robert Altman made “Gosford Park” he had 55 days to shoot a film involving 58 actors, who were often in group scenes. Because of this time constraint, Altman would usually light the entire scenes and have all the actors individually mic’d, with two cameras always moving among them. There was no time to get all the eye lines right or have the action to match from shot to shot – and no two takes were ever the same.

When film editor Tim Squyres first looked at the footage he said, “I thought I was losing my mind.” He definitely had his hands full and had to change his usual approach to putting a film together. He created multiple versions of scenes for himself and would ultimately ‘go prospecting’ to find the gems – the best moments and performances – and then finesse the cuts in a way to not disorient the audience. Although this was a tremendous challenge, Tim also appreciated that Altman was a brilliant choreographer of actors and behavior. He also understood Altman’s style, that he liked to shape problems into opportunities, to create a certain realism by having his audience lean in listen to the overlapped lines and off-screen conversations. Tim not only respected and ‘got’ Altman’s work, but he had the insight and discipline to ‘mine the richest veins’ from this unconventional way of shooting. The result was that the audience not only had fun with this who-dunnit film, they were also able to really immerse themselves in the upstairs/downstairs life that took place in a 1930’s English country estate.

Bobbie’s Upcoming Panel at EditFest LA: A Tribute to Two Trailblazing Editors

August 7th, 2:15 pm – 4pm

A Tribute to Two Trailblazing Editors: Dede Allen and Sam O’Steen.

My panel includes Jerry Greenberg, A.C.E. (“The French Connection,” “Apocalypse Now”), who was mentored by Dede and went on to achieve his own remarkable career and Carol Littleton, A.C.E. (“E.T: The Extra Terrestrial,” “Body …Heat”).

They will discuss the careers of Dede and Sam, as well show clips and

talk about their work on two seminal films from 1967: “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate.”

Recent News about Bobbie in Editors Guild Magazine

On May 13th I hosted a second event honoring editors at 92Y Tribeca. This time the editor was John Gilroy and the film we discussed and showed clips from was “Michael Clayton,” followed by a screening and Q & A discussion.